I didn’t grow up religious, but if my family had a church it was our sailboat. Every summer involved a month-long ocean pilgrimage up and down the coast of British Columbia, and like many churchgoing kids, the lessons I learned there wouldn’t become clear to me until much later in life.

I left the “family church” in my teens, and by my mid 20s I found a new religion: mountain hunting. My new church, where I would go to clear my head, gain perspective, and think about things that were bigger than me was wherever I pitched my tent or sat down to glass.

Every part of mountain hunting spoke to me, and over the years these wild places and intense experiences in the natural world struck a deep chord. Hunting created the space for me to slow down, observe, feel and appreciate mother nature more than I had ever done before. It completely changed my perspective of the natural world and how I interact with it. Instead of passing through, I was an active participant. Whatever our quarry of choice is, this feeling of connectedness seems to be a common thread amongst hunters I speak to.

In a world full of concrete and temperature-controlled buildings, I craved more of those intense wild experiences. Although B.C. has some long hunting seasons, it still didn’t offer year-round opportunities to chase that fleeting feeling that I had come to need. Where else could I chase that cathartic feeling during the off season? That’s when I rediscovered the old family religion.

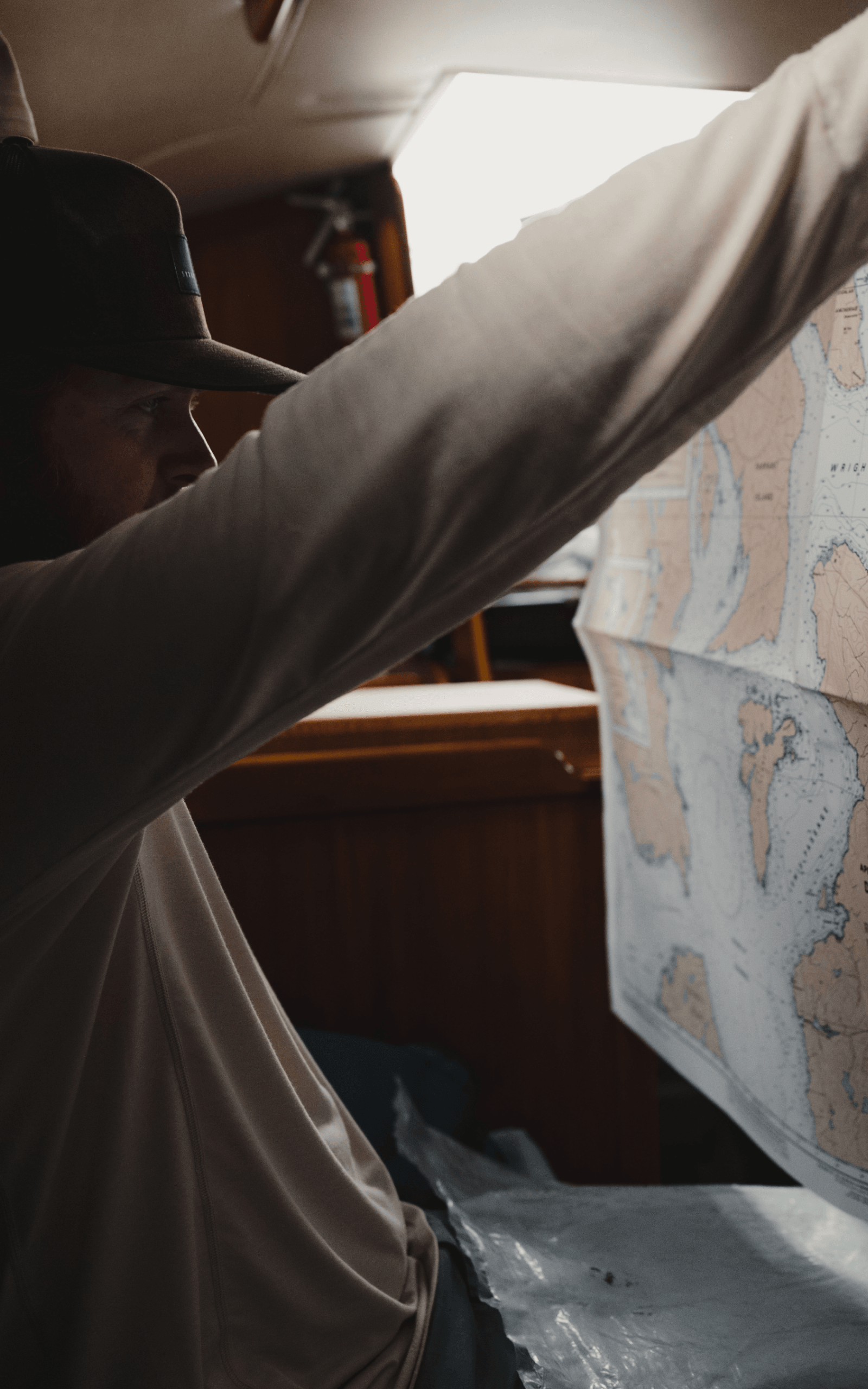

Sailing shares a lot in common with mountain hunting. Before either adventure there is a required component of prep and e-scouting and I look for almost the same thing in both: a productive harvest ground. Sometimes its mountain goat, sometimes spot prawns and sea urchins. And a secure place to hunker down for the night. The latter is quite a bit more finicky when sailing.

Sailing and solo hunting also both carry a certain amount of risk. The need to have your shit together when going into the mountains or out on the ocean is one and the same. There is a painstaking meticulousness that will often determine your odds of success as well as your ability to respond to an unexpected situation.

When I layer up or down on the mountain, my gear goes back in the exact same place in my pack every time. Likewise, every time I weigh the anchor or drop the sails, every component gets stowed in the exact same place in case I need it quickly next time.

Where these two worlds are most alike is in the way they are both hyper connected to the environment—the smells, the sounds and the feels. Both hunter and sailor are intensely tuned in to the slightest changes in wind direction or shift in the weather. Anyone who has spent much time on a motorcycle or in a convertible will know the feeling. Drive over a mountain pass and your cheeks freeze, rip through a desert and your nostrils fill with dust. You notice things around you that people travelling by other means wouldn’t.

No one has ever accused sailboats of being fast, and I would be lying if I didn’t say I wish I had a powerboat sometimes. But I am also aware that I would be giving something up if I did. Being in a slow-moving boat means needing to plan passages based on winds, currents and tides. If one of those isn’t in my favor then I have no choice but to wait for more favorable conditions or find another route. No different than being stuck in your tent on a mountain in a patch of zesty weather, you are at Mother Nature’s mercy and you don’t have a say in the matter. The need to work with nature is a humbling reminder of our place in the world, and it’s a lesson I cherish in the mountains and on the ocean.

The one area where sailing has mountain hunting beat is in the harvest. The ocean holds an undisputed advantage when it comes to variety of readily available protein. Depending on where you are, waking up in the morning with an empty fridge and having a seafood tower ready for happy hour isn’t a stretch. Not to mention cocktails on ice beat an electrolyte drink any day.

In recent years I have started to combine my passions which has yielded some mind-blowing results for me: sailing to remote islands off the coast of BC to chase Sitka blacktails or sea ducks, eating fire-cooked Dungeness crab and deer heart with my hands on the beach. These are the experiences that blow my hair back and ones that I will remember until my dying days. This is what life is all about for me.

I recognize that my church aquatic isn’t for everyone. Actually, it’s probably suitable for very few, but I would argue that by being hunters, by being connected to this most primal of pursuits, we have exposed ourselves to a way of life that offers a deep awareness of how curative wild places and wild foods can be. And once we have made that discovery it’s damn near impossible to turn our backs on it.

So what can a diehard hunter do when you start to crave that same experience after the season ends? Find a church that speaks to you. Grow your own food, master cooking over fire, train a hunting dog or build a box call. What I have learned is that despite how incredibly unique the hunting experience is to each of us, there is more than one way to scratch the periphery of the hunting itch in the off-season.