6.9.2025

Lōkahi

Hunting often takes us to remote corners of the world. More often than not, our interactions with the people who live in those places are fleeting—a gas station nod, a tip about the weather, or if we're lucky, a half-remembered story from a local over a beer in a dive bar, while an old tune crackles through even older speakers.

When we booked our flights to Hawaii to hunt and fish with Justin Lee, we figured it would be that kind of trip. A quick in-and-out. Four days to get our boots dusty and taste the salt, then back to reality. What we got was something far more immersive—a glimpse into a deeply connected ecosystem, and a community that welcomed us like old friends.

The Big Island was once the traditional home of King Kamehameha the Great and his temples still mark the coastline. Heading north from Kona, the desolate black volcanic fields shift into lush green pastures. Horses and cattle graze under big white clouds as the two-lane highway winds into the paniolo country—Hawaii's enduring cowboy culture. This land still pulses with the rhythms of ranch life, generations deep.

The forecast for our first day called for ideal spearing conditions, the kind you only get a couple times a year—rare wind and swell patterns that made a run to the North Shore possible. We woke just after midnight and met Justin’s friend and our captain, Asa, at the marina. By 3 a.m., we were underway. Cory, our underwater cameraman, slept on the floor of the boat, Justin curled up in the v-berth among dry bags and coolers and I laid on the motor box and watched the stars. The rest of the crew sat wherever they could, watching the lights of the harbor fade into nothing as we ran full throttle toward the horizon.

We spent the day fishing, crabbing, and listening. The three locals on board treated us like brothers. They explained the name of each fish we brought up, showed us how to sort Kona crab from the traps, and taught us—with the kind of patience that comes from generational knowledge and an eagerness to pass it along—how to dispatch an octopus with a bite. Their relationship with the ocean wasn’t recreational; it was ancestral and deeply engrained in who they are.

At 5,000 feet on the green shoulders of Mauna Loa, we visited Justin’s family’s forest reclamation project. The air was cooler there, the terrain steeper. Native sandalwood trees—fragile and slow-growing—competed with invasive species, while feral non-native goats and sheep moved across the rock and through the brush. We took a few animals off the land, knowing each animal removed would save countless saplings. This was hunting not just for meat, but to keep balance.

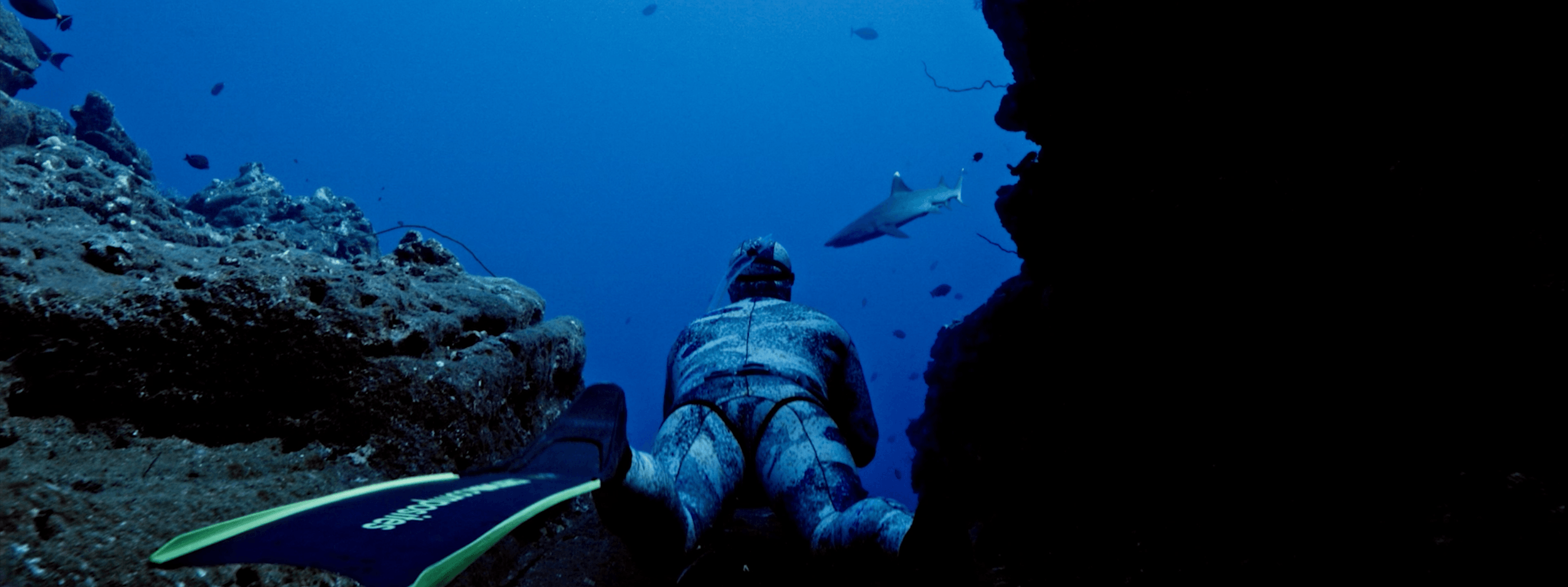

And that meat had a purpose. That evening, as the sun went down, our group of family and friends gathered to cook our catch and kills. Justin, his father-in-law, and I grilled sheep and octopus for a dozen friends and family. As we passed sashimi and charcoal rubbed backstraps, Justin told the story of spearing his biggest ever Ulua with us a couple days prior—his hands sketching the bend of his three-prong, his smile beaming as he relived swimming into the cave in pursuit of his target. The table leaned in. Not just to the story, but to what it meant. The appreciation was evident on all the faces around the table.

You can feel the ecosystem in Hawaii simply by driving from the sea to the summit—a landscape where fog becomes water droplets on a leaf, droplets fall to the ground, and rivers fall back into the sea. But the people are the connective tissue. Their warmth, their openness, their knowledge. Every hunting trip serves a different purpose, scratches a different itch. This trip was a lesson in community. A place where land and water, fish and forest, people and place, are all part of the same living thing.