Mike Mettler’s been hunting his family’s South Dakota farm his whole life, but he wasn’t the first to spot the enormous typical that would become the state record. Neighbors say they had seen him out on Mettler’s cornfield a few times, but Mike didn’t even know he existed until halfway through the 2013 rifle season. He saw the buck once or twice on his farm, and a number of times on his neighbor’s property, which has good cover. His neighbors were hard after this buck, but the busyness of life, work and family colluded to keep him from hunting much during the 2013 season. He didn’t even set up cameras, and thought maybe he'd never get a chance at him.

But the buck reappeared after the season with a few does, so for 2014, he put aside everything and dedicated himself to the buck. He put cameras out early and caught the buck coming onto his food plot and past the watering hole near his tree stand a few nights a week.

On opening day of pheasant season, Mike sat long in his tree stand. He knew everyone was hunting, and wondered if the buck would get spooked out of the cover of his neighbor’s property. No luck. He kept his eyes open the next few weeks, but only saw the buck twice, once just barely visible in the fog with several does, and once running with a big three point. His cameras caught him several times moving alone at night.

Then, on October 29, 2014—the day Mike and his wife welcomed their new daughter into the world—the camera caught the buck walking right under his stand in the last 15 minutes of shooting light.

“Seeing the photos, I thought I had missed my shot at this buck,” he said.

At noon the next day, the Mettlers brought home their new baby girl. His wife said, “Go," and Mike haunted his tree stand for almost a week straight, but saw no sign of the monster in the fields or on camera.

“At that point, I figured he had either moved out of the area or someone had taken him,” he said. “The last week before rifle season, having not heard of anyone taking the buck, I decided to stick with it, and if I didn't see him, I'd try again during rifle season.”

That week it got colder. The watering hole froze over, and he knew that unless they were rutting, there was no reason for any animals to come near his tree stand.

But it was windy enough, and Mike likes spot-and-stalk hunting better than sitting in a stand. Plus he was already wearing Open Country, the pattern scientifically developed for on-the-ground engagement, so it only made sense to get down and creep through the cornfield.

“I’ve been using Sitka Gear for the past three years, and it outperforms anything else I have worn. I do a lot of spot and stalk in harsh weather, and I’ve had deer literally look right through me.”

That confidence was about to pay off. After some time working the edge of the cornfield, he caught sight of a doe 50 yards away and stopped. Then, four rows away from her and 15 yards closer, a rack appeared, poking out of the corn. This was the one, bedded in the thick stalks.

Mike wanted closer, but he was in full view of the doe and decided not to risk it. So he waited in the cold wind, arrow nocked, ready. After 40 minutes, the doe started to move off, and the buck stood.

“That was when the buck fever kicked into high gear,” he said. “I'm not real sure how I got my release hooked onto my loop, but upon releasing the arrow I heard a WHACK and I tried to look through my binoculars, but quite honestly, I couldn’t even look through them. I was shaking so bad!”

Mike waited for 40 minutes before he started tracking. There wasn’t much blood and the trail was hard to follow. He scoured the plot but couldn’t find the buck anywhere and got in his pickup thinking maybe the buck ran out into a cut section.

“At one point I saw a buck with a bunch of does. My stomach turned thinking I might have hit him too far back. I figured I’d have to wait ‘til morning and then come get him,” he said.

But as he watched, it became clear this wasn’t his buck. He parked and walked the plot again, his eyes darting this way and that looking for any trace of blood. Soon, he found a few specks that seemed to indicate the buck had gone east, and Mike followed. As he came over a small hill, he saw him there crumpled and still.

“I didn't know whether to be excited or relieved. The buck that had absolutely consumed me for over two years was at my feet,” he said.

Mike looked the buck over and saw that the quartering shot had hit the far shoulder blade, which stopped the arrow from passing through. A simple explanation for the lack of blood.

The explanation for how he came to be the one who took such a magnificent animal was a little more complicated. His neighbors had the buck on camera as much or more than he did, and the buck had been bedding on their property. They had food plots like his, but it seemed the buck went where the does went, and on that day, it happened to be his plot. You could chalk that up to luck.

But then there was the season prior, when the busyness of life wouldn’t let him hunt hardly at all, and he knew if he’d had things his way, the buck wouldn’t have grown another year. Was that luck too?

Then there was this year, the birth of his daughter, the generosity of his wife letting him put 180 hours in the stand in a month’s time. His dedication, determination, the change in the weather letting him hunt his favorite way, the arrow finding its target, the shakes. It seemed like so much more than luck.

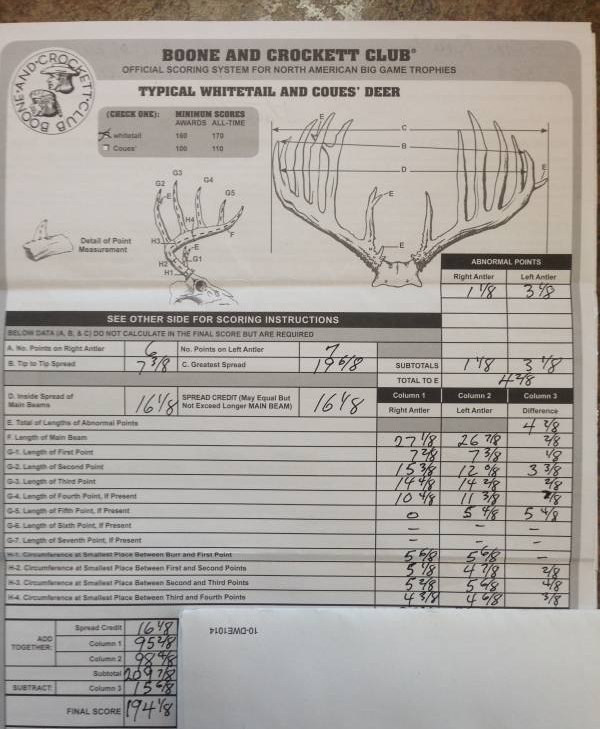

After a 60-day drying period, a Pope & Young official scorer measured the buck at 194 1/8 net inches (209 7/8 gross). That surpasses South Dakota’s former state archery record of 182 7/8, and also edges out the firearm record – set in 1948 – of 193 2/8, making Mettler’s buck the largest typical whitetail ever taken by a hunter in South Dakota.